|

FEATURE

Leveraging AI to Enhance Grant Writing

by Kevin Leary

| If you are going to use AI to support your grant writing initiatives, you need a proper blueprint to do so effectively. |

AI is a topical point of conversation in most professions today, and people are continually exploring opportunities to apply AI to their various job requirements. From drafting emails, to summarizing text, to taking meeting minutes, AI is being leveraged to save time, create efficiencies, and reduce effort in everyday work life. According to a comprehensive article from the Harvard Business Review, there are a top 100 set of use cases for large language models (LLMs); the article distills them into six key themes from tens of thousands of online posts in business and daily life (Zao-Sanders 2022). The research highlights the many ways LLMs are being used as capacity enablers by professionals for technical assistance and troubleshooting (23%), content creation and editing (22%), personal and professional support (17%), learning and education (15%), creativity and recreation (13%), and research, analysis, and decision making (10%).

These themes get to the crux of AI’s impact as a time-saving mechanism. The importance of time as a currency is a fundamental economics tenet and, in some cases, time is seen as more valuable than money because “you can use your time to make money, but you cannot use money to purchase more time” (Harvey 2010). Keeping this paradigm in mind, while somewhat self-evident, helps to rationalize the inescapable, topical AI craze we are seeing. This is especially true in the context of grant writing, which is a time-consuming and labor-intensive process, but one that is an essential mechanism for institutions of higher education and academic researchers to fund programming, research, and projects (Godwin et al. 2023).

With that being the case, this article captures the sentiment of using AI in the grant and academic writing landscape as well as how early adopters are applying AI to this technical process. It also provides an overview of a useful AI-supported tool that can help augment the research aspect of grant writing, which is a common component when looking for project rationalization and evidence-based practices.

AI Adoption in Grant and Academic Writing

According to a Nature survey of 1,600 researchers around the world, responses indicated that 25% of researchers use AI to help them write manuscripts, and more than 15% use AI technology to help them write the actual grant proposals (Parrilla 2023). The survey (Van Noorden and Perkel 2023) also showed that two-thirds of respondents said AI provides faster ways to process data, 58% noted that it speeds up computations that were not previously feasible, and 55% mentioned that it saves scientists time and money. Even among those whose use of generative AI is sparse or tentative, some anticipated a transformation of their professional lives through more efficient and economical ways of working and a reduction of administrative burden (Watermeyer et al. 2024).

Given the finite nature of time, the stringent deadlines of requests for proposals, and competing priorities in terms of the many facets of grant applications (abstract, budget, letters of support, supplemental forms, etc.), the grant writing process necessitates a triage-focused approach in which high-value tasks receive the most attention, and opportunities to expedite clerical tasks are capitalized on where appropriate and allowable. The use of AI in academic writing can generally be divided into two broad categories: 1) those apps that assist in the writing process and 2) those used to evaluate and assess the quality and validity of written work (Golan et al. 2023). Some of the common applications of AI in the grant writing process include text summarization, generation of outlines, creation of research protocols, simplification of jargon-laden paragraphs, improvements to the clarity and conciseness of drafts, language translation, and drafting informed consents, emails, letters of support, reports, and other written documents (Golan et al. 2023 and Seckel et al. 2024). In one accounting of personal usage, the user “asked ChatGPT to write a paragraph explaining how our proposed research fitted the funder’s call. Again, the chatbot did a great job. I read through everything, changing a few parts where the use of ChatGPT was too obvious. It cut the workload from three days to three hours” (Parrilla 2023). Used properly, AI can drastically reduce time spent on certain tasks, but not autonomously. Problematically, AI technology has produced research abstracts that were good enough that scientists found it hard to spot that the content had been written entirely by AI (Editorial 2023).

What Paradigm Should You Use When Applying AI to Your Grant Writing?

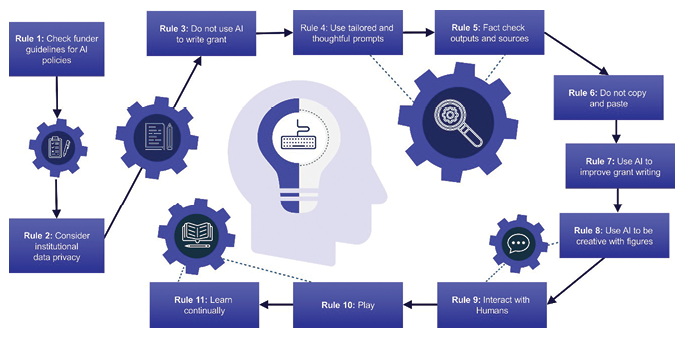

If you are going to use AI to support your grant writing initiatives, you need a proper blueprint to do so effectively. In the image below are guideline rules on how to leverage AI in grant writing as suggested by a group of researchers (Seckel et al. 2024) in the PLOS Computational Biology journal. The authors discuss key considerations in terms of funder expectations regarding AI, the importance of data privacy limitations, and other guiding principles that should be considered at different points of the grant-application process. Chief among the rules is that AI should not write your grant, and copy and pasting AI-generated text should be avoided. They also bring up the important point that writers should not forget to solicit feedback from traditional intelligence—colleagues and peers.

The following rules are straightforward and provide excellent guidance on the do’s and don’ts of AI assistance in grant writing. (These rules are derived and adapted from the aforementioned Seckel et al. article, but the commentary is my own.)

|

| The rules for using AI tools in grant development |

Rule 1: Check the Guidelines of the Funding Agency Regarding AI

This is an absolute must. First, confirm if AI is allowed. If so, are there any parameters about your usage, such as a disclosure statement?

Rule 2: Consider Data Privacy Limitations

Do your best to avoid putting your own fully formulated ideas or projects into LLMs, which could then be used by competitors or violate your own institutional policies. Any sensitive data from your institution should not be put on an external platform.

Rule 3: Don’t Use AI to Write Your Grant

You should not permit AI to generate large pieces of your proposal, for both technical accuracy and ethical reasons. This is paramount because you could risk your proposal being flagged for plagiarism. According to academic journals such as Nature and Science (Lee 2023), AI is not allowed to be a co-author on publications, from both a copyright and research ethics perspective, and should not be a primary or main contributor of your content. Although AI cannot be a co-author, new guidance from APA (grammarly.com/blog/ai-citations-apa) has been issued on how to cite AI-generated content (Ellis 2023).

Rule 4: Use Custom Prompts for Specific Feedback

To take advantage of AI, you need to be adept at composing prompts to elicit the right output that is specific to the vision you have for your grant. I have found it helpful to focus on the topic of the grant and who the funder and key thought leaders are in the field and by being specific about the task I need support with, such as finding academic research based on recency or drafting a set of survey questions to measure program impact using a Likert scale.

Rule 5: Fact-Check Everything

Much like humans, AI is fallible. Double-check the outputs of your AI, and use shrewd prompts that ask for source information and the justification or rationale used to generate the outputs. If you cannot locate the provenance of the output or data, you should question its authenticity.

Rule 6: Don’t Copy-Paste; Use the AI-Generated Text as Inspiration

It is not just imperfection you should be concerned with when it comes to using AI-generated text as is. LLMs can often take significant chunks of existing text, which could flag your application for plagiarism and disqualify your work (Seckel et al. 2024). Without proper prompts, it can also generate content that looks good on the surface but lacks the substance necessary for a competitive grant application.

Rule 7: Use This Iterative Process to Become a Better Grant Writer

Understanding how AI has generated the content in terms of creation, revision, and summarization can allow users to improve their own writing ability. This is a reversal of traditional reinforcement learning, which is fundamental to machine learning (Seckel et al. 2024). This includes how the tool was effective or ineffective.

Rule 8: Use the AI for Inspiration in Developing Figures

AI is not limited to text-based outputs. It can find new and creative ways to present data and diagrams that could help to make your content stand out. It can also help with interpretations of data that you may not have considered (Seckel et al. 2024). Playing off Rule 7, you can use this as a brainstorming or creativity exercise to ideate possible ways to present your grant information.

Rule 9: Don’t Forget to Interact With Humans

It is not enough to have your own eyes review the outputs of AI-generated content. As the party who prompted the content to begin with, it would be wise to get an outside perspective to make sure there is still comprehension and that it resonates with the content being put forth in the grant application.

Rule 10: Play!

AI is a new frontier and a new tool to enhance and enable capacity to produce high-quality grant applications. Those who adopt this tool responsibly have the opportunity to improve key areas of their submissions and improve performance in a highly competitive environment, thereby improving their likelihood of being selected for funding. Much like the AI models, you should continually fine-tune your approach based on the success of AI tools as well as which tools are better for which tasks.

In a follow-up to Rule 10, I am proposing an additional rule in the same spirit:

Rule 11: Learn Continually

There are no shortages of new tools that are available. They have a variety of features and even some pitfalls. For example, ChatGPT and Copilot are better tools for image generation, and Google Translate and DeepL are better at language translation. Knowing which tools are most suitable for which tasks can help you maximize the utility and reliability of your AI outputs.

You should not only be on the lookout for new ways to apply the technology, but when it comes to grant writing, you should be on the lookout for new rules that impact your ability to utilize AI. In the past year alone, the number of AI-related regulations in the U.S. rose 56.3% from the just 25 AI-related regulations in 2023, and funders are monitoring whether their policies are sufficient to manage AI and its impact on grant applications (Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI 2024). If you found these rules beneficial, you may also be interested in the GitHub repository Seckel et al. created (github.com/eseckel/ai-for-grant-writing) to collate and curate resources on this topic. It includes prompt resources and suggested LLM tools, as well as their useful application in reviewing, composing, and translating content to help other grant writers leverage AI for their submissions.

AI Supported Research Tool—Semantic Scholar

One AI tool that I have found particularly useful in supporting grant writing is Semantic Scholar, developed by the Allen Institute for AI. This tool is focused on finding a better way to search and discover scientific knowledge, and it provides free, AI-driven search and discovery tools and open resources for the global research community. It indexes more than 200 million academic papers sourced from publisher partnerships and data providers. They are available through its AI-supported navigation tool.

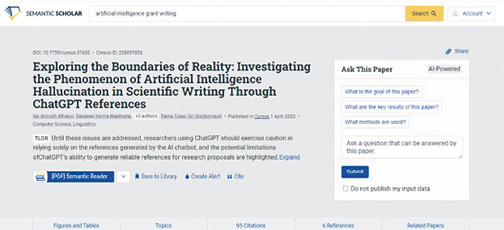

Identifying the citations to support your project’s rational or logic model is a crucial component of the grant application process and can be a time-consuming endeavor. Because of this, Semantic Scholar offers a way to save time with its TLDR (too long, didn’t read) description summaries, which are AI-generated directly from the source material.

TLDRs (semanticscholar.org/product/tldr), which can be seen in the image below, are concise summaries of the main objective and results of a paper, generated using expert background knowledge and natural language processing techniques. They are available for approximately 60 million papers across computer science, biology, and medicine. Let’s discuss some of the key functionalities of Semantic Scholar that you may find useful.

|

| Screenshot of search page of the Semantic Scholar website |

Check Highly Influential Citations

You can see Highly Influential Citations (semanticscholar.org/faq#influential-citations) that were referenced in the publication and had a significant impact on the content. They are based on a machine-learning model that analyzes influencing factors, including the number of citations to a publication.

Cite Any Paper

Any paper you find relevant for your research can have the appropriate citation provided through Semantic Scholar’s cite feature, including BibTex, MLA, APA, or Chicago styles.

Tips to Get Better Recommendations

You can rate the content output by your inquiries to teach Semantic Scholar’s AI what is or isn’t relevant to you. The more ratings you submit, the more relevant your recommended papers will be.

Create Library Folders

You can add five relevant papers to a library folder to help record your research. Semantic Scholar will also show you papers that are similar to those saved. This is helpful when you are working on multiple grant applications and want to stay organized by funder or topic.

Narrow Your Search Scope

You can also mark three nonrelevant papers as “not relevant” in your Research Feed, and Semantic Scholar will show you fewer papers similar to these.

Proactive Topical Updates

Once you have been searching certain topics, Semantic Scholar can send you a weekly digest with similar articles that you have reviewed featuring the TLDR overview. n

|

Resources

Editorial. (Jan. 24, 2023). “Tools Such as ChatGPT Threaten Transparent Science; Here Are Our Ground Rules for Their Use.” Nature. doi.org/ 10.1038/d41586-023-00191-1.

Ellis, M. (July 6, 2023). “How to Cite Artificial Intelligence in APA Style.” Grammarly. Retrieved July 23, 2024. from grammarly.com/blog/ai-citations-apa.

Godwin, R., DeBerry, J.J., Wagener, B.M., and Berkowitz, D.E., and Melvin, R.L. “Grant Drafting Support With Guided Generative AI Software.” Available at SSRN: ssrn.com/abstract=4594509 or dx.doi.org/ 10.2139/ssrn.4594509.

Golan, R., Reddy, R., Muthigi, A., and Ramasamy, R. (2023). “Artificial Intelligence in Academic Writing: A Paradigm-Shifting Technological Advance.” Nature Reviews Urology, 20, 327–328.

Harvey, M. (Dec. 29, 2010). “Time Is More Valuable Than Money.” Stanford eCorner. Retrieved June 7, 2024. ecorner.stanford.edu/articles/time-is-more-valuable-than-money.

Lee, J.Y. (Feb. 27, 2023). “Can an Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Be the Author of a Scholarly Article?” Journal of Educational Evaluation for Health Professions, 20(6). doi.org/10.3352/jeehp.2023.20.6.

Parrilla, J.M. (2023). “ChatGPT Use Shows That the Grant-Application System Is Broken.” Nature (London), 623(7986), 443–443. doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03238-5.

Seckel, E., Stephens, B.Y., Rodriguez, F. (March 1, 2024). “Ten Simple Rules to Leverage Large Language Models for Getting Grants.” PLOS Computational Biology, 20(3): e1011863. doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi .1011863.

Semantic Scholar. (n.d.). TLDR. Retrieved July 15, 2024. semanticscholar.org/product/tldr.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI. (2024). “Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2024.” Stanford University. Retrieved from aiindex.stanford .edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/HAI_AI-Index-Report-2024.pdf.

Van Noorden, R., and Perkel, J.M. (Sept. 27, 2023). “AI and Science: What 1,600 Researchers Think.” Nature, 621(7980), 672–675. doi.org/ 10.1038/d41586-023-02980-0.

Watermeyer, R., Lanclos, D., and Phipps, L. (Jan. 22, 2024). “If Generative AI Is Saving Academics Time, What Are They Doing With It?” LSE Impact Blog. blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2024/01/22/if-generative-ai-is-saving-academics-time-what-are-they-doing-with-it.

Zao-Sanders, M. (March 19, 2024). “How People Are Really Using GenAI.” Harvard Business Review. hbr.org/2024/03/how-people-are-really-using-genai.

|