FEATURE

Ebook Availability, Licensing, and Pricing in Canada and the U.S.: A Follow-Up Study

by Michael Blackwell, Jennie Rose Halperin, Catherine Mason, and Carmi Parker

| [The current study’s] focus on bestsellers and notable fiction and nonfiction provides a fairly accurate idea of what librarians face when selecting and maintaining digital content in 2025. |

In 2018, Rebecca Giblin and her colleagues created the E-lending Project, measuring in various studies the availability, license terms, and prices of digital titles in Australia. Additionally, using one library vendor, it internationally compared digital findings to print in various ways.1 Members of the ReadersFirst Working Group were intrigued. We mounted a follow-up study looking at the three vendors with the most public library market share in Canada and the U.S. to compare them in title availability, licensing type, and cost in order to take a snapshot of the library digital market, especially how it compared to library options in print books.2 In the last 5 years, many changes have occurred in the library ebook market. This follow-up study measures the effects of those changes and assesses whether library selectors are seeing any improvement in our ability to build collections that are varied, deep enough to support reasonably quick access to popular titles by patrons, and sustainable over time—at least when compared to our print collections.

Libraries have more options for digital licenses than in our previous study. In 2018, ebook licenses ranged from perpetual (that is, accessible forever, or at least as long as the publisher holds the license, though one does well to be suspicious if such licenses truly are lasting) through various forms of metered, with 26 checkouts or 2 years of circulations being the most common. Now, though far fewer ebook titles are available in perpetual access, with all Big Five publishers having gone to metered only, more metered options exist on many titles, from a five-circulation model up to 40 (with 10 allowed simultaneously) or even 100 circulations allowed simultaneously. From one Big Five publisher, Penguin Random House, 1-year or 2-year options for the same title are available for ebooks, with 1-year or perpetual options for audio. We welcome these options, even as we decry the loss of many ebook options for perpetual access. More numerous models complicate ordering—and, for the purposes of our study, factoring effective cost—but they do allow libraries to better allocate limited resources to get the best return.

Our original study looked only at ebooks. For this study, we also looked at audiobooks to account for their growth in use and importance in library collections. In 2024, they made up about 43.1% of digital book circulation, growing 19% that year alone.3 We will make some comparisons of title availability and license type (including cost) among vendors to see if there is any variation, but vendor evaluation is not our aim. Our primary aim is, again, to provide a snapshot of the library digital market, measuring how digital collections compare to print in title availability and cost and to consider how those factors affect collections.

The data forces us to conclude, reluctantly, that not only does print still offer libraries a far better bang-per-book than digital, but that for most popular titles, digital collections are becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. Some smaller and independent publishers are, however, now more likely to be present in the market and offer some hope for long-term and cost-effective holdings.

Study Scope

Selection of Vendors

Our current study looks at four vendors for the U.S. and three for Canada and focuses on the public library market and not academic or school library collections. Further study of those markets would be of interest. We have not studied all public library ebook vendors. Including all of them would, perhaps, change results slightly. For both countries, we have included the market leader, OverDrive. Another established vendor with many clients—OCLC’s CloudLibrary—is included, although this platform has gone through many owners. A more recently developed nonprofit option—the Palace Project from Lyrasis—is included. It is new to Canada and only 3 years old in the U.S., so its title coverage may be more limited. Its many unique licensing options make for an interesting addition. For the U.S. only, we looked at Midwest Tape’s hoopla. This platform is more typically used for pay-per-use, with titles available for download always, but costing the library for each download. That pay-per-use model is difficult to compare with the other vendors. We have not studied it, especially since several of our member libraries are finding it increasingly cost-prohibitive. Instead, we looked at its more traditional licensing options, not yet widely used in Canada.

Selection of Titles

Titles were chosen from August 2024’s The New York Times and Toronto Star hardcover lists for fiction and nonfiction, The Washington Post paperback list, and Amazon Kindle bestseller lists. Additional selections were made from the past 5–10 years of Giller Prizes, Governor General’s Literary Awards, Pulitzer Prizes, Booker Prizes, Hugo Awards, Romance Writers of America’s RITA Awards, and the Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Awards. Some Pulitzer and Giller winners from the 1980s or 1990s from both countries were included to test for coverage and license of older works. Nearly all titles would be a likely license by most public libraries and certainly all large ones—although some Canadian libraries might not acquire some more U.S.-specific titles and vice versa. While it is a compelling read, Bill Waiser’s A World We Have Lost: Saskatchewan Before 1905 might not be of interest in many U.S. libraries, while many Canadian libraries might be less interested in the U.S.-centric politics of Pete Hegseth’s The War on Warriors: Behind the Betrayal of the Men Who Keep Us.

To get a sense of the variation in price between Big Five and other publishers, effort has been made to sort out who provides what, but separating the Big Five holdings from others in digital is complicated by two factors. First, some publishers (for example, McClelland & Stewart) have older titles listed as non-Big Five and other titles listed as Big Five, reflecting the fact that they have been gobbled up. The once-independent titles, if licensed now, would all be under the Big Five terms. Second, some smaller publishers (for example Seven Stories) work through large publishers for ebook distribution, and they are compelled to license under Big Five terms, no matter what their preference.

Originally, 200 titles were selected. A member of the ReadersFirst Working Group asked that four recent, popular titles be added, bringing the total to 204. Most titles are fairly new—63 titles (31% are from 2023 to 2024)—and are likely to be in high demand in most public libraries. About 69% are fiction of many genres (fantasy, general, historical, literary, mystery, romance, sci-fi, and thriller), while 30.9% are nonfiction. Originally, 147 (72%) were published by the Big Five, while 160 are released by the Big Five, reflecting both some smaller publishers distributing through the Big Five or the Big Five having subsumed some publishers now releasing digital as subsidiaries.

The current study is meant to be suggestive and not a complete picture of the library digital ecosystem. That said, its focus on bestsellers and notable fiction and nonfiction provides a fairly accurate idea of what librarians face when selecting and maintaining digital content in 2025.

Title Availability

Print Titles

All of the titles on our list would be available to consumers if the full range of resources—online vendors and secondhand sellers—were used. Many libraries have these options, and certainly most libraries could get all of the titles, if only in very good used condition. However, to provide a more appropriate comparison between print and digital in terms of what libraries would typically order new, we have restricted availability to new titles that library jobbers can provide. Interestingly, the jobbers still have access to books that seem to be out of print in retail outlets. They can provide them, but generally not at the discount that is usually offered. The explanation seems to be print on demand. Our jobbers have told us that they expect this feature to be ever more common, with new agreements perhaps even allowing access to titles not originally available in a country under copyright. Selections were in hardback whenever possible, since they are more durable. Trade paperback choices were necessary in some cases, as were mass-market releases. We used only one print jobber per country. Our aim was not to rank print jobbers. We note that fact here to indicate that print availability might be even higher than our study suggests if we looked at all possible jobbers.

In the U.S., 195 of 204 titles were available through the library print jobber. Seven of the nine were also unavailable through retail outlets, likely for copyright reasons since they were not originally published in the U.S. Two of the nine were from a U.K. publisher, six were Canadian, and one was from the U.S., but was indie-published (and on the list because of its presence on the Amazon bestseller list). Overall, 95.6% of the titles are available to libraries through the jobber.

In Canada, 196 of the 204 titles were available through the jobber. Six of the eight unavailable titles were also not available through retail outlets, with copyright across borders again seeming to be the primary reason. Between both countries, only one title—an indie-published one—was not available for libraries by jobbers (though it was available in the U.S. via retail). Ninety-six percent of the titles were available to libraries by the jobber.

Digital Titles

Across all vendors in the U.S., 185 of the 204 selected titles are available to libraries in ebook format (90.7%), with nine being unavailable.4 Canada fares four titles better: Across all vendors, 189 titles (92.6%) are available as ebooks, with 15 not available. The results are not quite as good for audiobooks: Across all vendors in the U.S., 161 are available (78.9%), with 43 unavailable. In Canada, 159 (77.9%) are also available in audiobook format, with 45 unavailable.5 Titles are more readily available to individual consumers: 191 in the U.S. and 188 in Canada. Several factors seem to be in play for title availability, but not all appear to be significant.

Unlike in our previous study, title age is not a factor, at least in this title selection for ebooks. In our previous study, only 60% of older titles were available. In both the U.S. and Canada, of 18 books published before 2000 (8.8% of all titles), across all vendors, only one title was not available; 94.5% were available. Libraries do not fare as well in audiobooks: Only nine of the 18 titles from before 2000 (50%) are available in Canada, while seven are in the U.S.6 Of the 34 published before 2016, 15 are not available in the U.S., and 18 are not available in Canada.

The type of book also does not seem to be a significant factor. Those ebooks not available in the U.S. are a mix of fiction and nonfiction—but mostly fiction—with the only striking figure being that six of the 21 are in the romance genre. At least for the titles considered here, these are more likely to be indie or mass-market published or to have been published outside the U.S. and so are less likely to be available in digital. In Canada, 12 of the 15 unavailable titles are fiction (five of them romance), with other factors again explaining the presence of those. In audiobooks, both countries have an even mix of what is not available, with a mixture of fiction and nonfiction, and no one genre seeming to be disproportionately unavailable.

The country of publication—and hence, copyright contracts across borders—and publisher size are bigger determinants than is publication date in ebooks. Fourteen of the 21 unavailable ebook titles in the U.S. are from non-Big Five publishers. Eight are from the Big Five, but seven of those originated in Canada or the U.K. All told, 15 of the 21 were published outside the U.S. In Canada, only two of the 15 unavailable titles are from the Big Five, and one is not available in ebook format anywhere. Thirteen are from smaller or indie publishers. Eleven were not published in Canada.

Another factor is at play in audiobooks: 30 titles seem never to have been released in audio in libraries, at the time of this writing. In addition to age, a lack of perceived consumer interest by the publishers seems to be at work. Canada has nine unique titles, and the U.S. has five, so the country of publication likely does play some part. There are surprises: We would have thought that Margaret Atwood’s Alias Grace would be available in audio in the U.S. It is not. Twenty-four of the unavailable 45 U.S. titles are from the Big Five, while 21 are not. In Canada, 21 unavailable titles are from the Big Five. Interestingly, 26 titles from smaller and indie presses are listed as distributed by Lightning Press, Inc.—a print-on-demand company. It would seem that ebook vendors are also benefiting from this trend.

Only two titles are available to libraries in audiobook that are not available in ebook. One seems an anomaly: Peter Taylor’s Pulitzer Prize-winning A Summons to Memphis. It is not available in ebook format even to the public, but it is offered in many license varieties in audiobook. We might expect this title to have as much, or more, appeal in ebook. Did the author or heirs at some point stipulate that it should never appear in ebook format? Freida McFadden’s Never Lie is from the indie publisher Poisoned Pen. It is commercially available as an ebook. Why it isn’t available to libraries is a mystery. We encourage small publishers to look at the library market.

Licensing Terms Licensing Terms

Ebooks

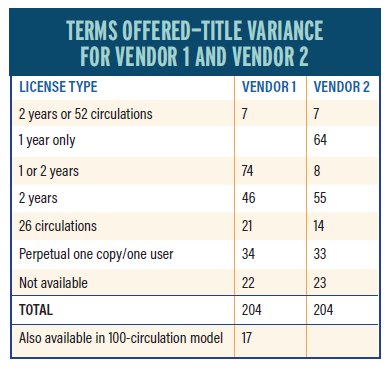

Our previous study found few discrepancies among the vendors on the basic license types. One vendor might have offered a book on perpetual access, while another had it metered. In this new sample, discrepancies remain at about the same level. If one vendor offers Penguin Random House ebooks in its standard 1-year or 2-year metered terms, the rest generally also do. In the U.S., there are exceptions on only five titles. One vendor, which is newer, offers two titles on a metered basis that others offer on perpetual. The cost for the metered license is lower than for the perpetual. The titles came from a publisher that used to offer perpetual but that has been taken over by a Big Five metered-only publisher, with the older license holding sway with the older vendors. In a pleasant surprise for librarians, however, there is substantial variety because of the addition of variable license terms. In ebooks in the U.S., 20 (10.8%) titles vary. Seventeen of those result from one vendor offering a 100-circulation model (with simultaneous use by many readers) in addition to a perpetual or an additional metered option. This model is only offered on somewhat older tiles—2022 and earlier. Another—again, the newer vendor—offers both a perpetual and metered license on three titles, while the others offer only metered. These differences seem to result from vendors negotiating different deals with publishers. The outcome is considerable variation. For example, two vendors with similar overall holdings had the breakdown shown in the table to the left.

The biggest discrepancy is due to Vendor 2 offering only a 1-year license on Penguin Random House titles when Vendor 1 (and the other vendors studied) offer both 1-year and 2-year licenses on them.

Not all of the news is good. Of the available titles, 150 are published or distributed by the Big Five. Of those, only eight are perpetual one-copy/one-user terms—those date from earlier years (1985–2011) and are from publishers that have either been subsumed or that are smaller and distributed through the Big Five. Smaller and indie publishers are more likely to offer perpetual terms. Most of their available titles are perpetual: 27, with only nine metered. All told, 153 titles of 185 available titles (82.7%) are metered, while 35 are not. Of the metered titles, 131 are metered by time and 22 by number of circulations. For the purposes of this calculation, the six 2-year or 52-circulation (whichever comes first) licenses are counted as 2 years, which is the most likely result. The 17 listed on the chart as “also available in 100-circulation model” are not double counted.

Canadian ebook results are similar, apart from the significant difference that even a higher percentage of the available titles are metered. Across the Big Five holdings, there is no variation in licensing across the vendors. One vendor again offers 13 titles in a metered, 100-checkouts model, down somewhat from the 17 in the U.S. A great discrepancy exists between Vendor 2 and the others because it offers only 1-year (and not both 1-year and 2-year) metered models. On some smaller publisher holdings, Vendor 3 offers metered and perpetual models on two titles where the others offer only perpetual, and in one case, the vendor offers only metered when the others offer perpetual. The majority of the 189 available ebook titles are metered (161 or 85.18%), with only 28 (14.82%) being perpetual. Of those 28 perpetual titles, 26 are from smaller and indie publishers.

Audiobooks

Audiobooks are even more varied than ebooks in licensing terms available. In the U.S. among all four vendors, there is little variation in basic licenses for Big Five or smaller publishers. Hachette and Simon & Schuster offer 2-year metered access, for example, and all four vendors have no variation on their available titles. We found only four variations on basic licensing across all titles for all vendors. Where the variety occurs is in additional license options. Vendor 1 offers 43 titles in the 100-circulation, one-user-at-a-time model. Vendor 3 offers multiple models on five titles: perpetual access one-copy/one-user, metered for 2 years, 2 years with 40 circulations (up to 10 concurrent), five circulations (all of which may be concurrent), or 55 circulations one user at a time. To give an idea of the variety that can occur, consider John Kennedy Toole’s A Confederacy of Dunces (1981) in the U.S.: One vendor offers it not at all, another in perpetual access only, another in perpetual and metered by 100 circulations, and another still in perpetual access, metered by 2 years, or metered by 40 loans, 10 of them concurrent. Penguin Random House offers a 1-year metered model or perpetual access on all of its titles (except oddly for just one, which is only perpetual); however, on those titles, Vendor 3 offers only the 1-year option and none in perpetual access.

Licensing Types and Variation Between Vendors

- This study’s 92.6% ebook availability in Canada and 90.7% availability in the U.S. eclipses the previous study’s 84.2%. Publishers, and with them library vendors, may be closing the gap with print availability.

- Big Five ebook titles are available at nearly the same rate as print from library jobbers. Smaller press/indie titles are slightly less likely to be digitally available but more likely than they were 5 years ago.

- Libraries should be able to offer most newer and high-demand titles in ebook format. Our ability to build a robust ebook collection, at least as far as availability goes, is nearly equivalent to what we offer in print.

- Smaller and indie press titles are slightly less likely to be available in ebook format and even less so in audio.

- In audiobooks, date and publisher perception of monetary value create less availability than with ebooks. No doubt the added production costs are a factor. We lament that many interesting works may not be available in this increasingly popular format. Libraries do not currently have as much scope for collection building in audio as in print or ebooks. For printdisabled patrons, books made into noncommercial audio under the Marrakesh Treaty or by special libraries for the visually disabled may close this gap.

- Print on demand seems to enhance title availability in both print and digital holdings in smaller or indie publishers, a trend we are pleased to see.

- Two titles are available in digital that are not readily available in the U.S. through the print jobbers: Five Wives by Joan Thomas (2019) and Sing Me a Secret by Julie Houston (2020). They are available in Canada. Their place of publication—Canada and the U.K.—seems to be the reason for their lack of availability. We are pleased that subsequent licensing agreements in digital may be able to increase title availability across borders.

|

The Big Five publish or distribute 131 of the 161 (81.4 %) available audiobook titles, offering 101 perpetual licenses among them (77 % of their available titles), with metered only on 20 (23%). Notably, Penguin Random House offers a metered 1-year option and perpetual-access option on nearly all of its titles, with vendors striking a few different deals, especially on older titles from presses that may have been subsumed. We are including those as perpetual in this count.

The smaller publishers offer 30 titles, but every one of them is available for perpetual access from at least one (but not every) vendor. Of the 26 metered titles (not counting the 43 that have an additional 100-circulation option in addition to other options), all have a 2-year loan period. Total percentages for all titles in perpetual are 81.4%, and metered is 18.6%.

Canadian offerings are largely similar. The same number of titles are available, but the titles are not all the same ones. Unfortunately, perpetual access is less than it is in the U.S. Vendor 1 offers 39 titles on a 100-circulation, one-use-at-a-time metered model. Vendor 3 has only just started its Canadian operations but has begun with varied offerings: Six are on a 55-circulation model, three have a 40-circulation/10-concurrent model, and one has a 15-circulation/five-concurrent model. Of the 161 available titles, 132 (81.9%) are from the Big Five, and 99 (or 75%) of those are offered in perpetual license, with the Penguin Random House titles being counted as perpetual for this purpose. Thirty-three (25%) are metered only. Smaller publishers provide 29 of the available titles. Twenty-five of those are available in perpetual license (86.2%). In total, 124 of 161 available titles are available in perpetual license (77%), while 37 (23%) are metered only.

Canada and the U.S. show similar trends in ebook and audiobook licensing, with Canada lagging slightly in perpetual audiobook percentage (see the chart and the sidebar).

Costs

Print Costs

Our study always uses U.S. dollars for titles in the U.S. and Canadian dollars for those titles available in Canada. We do not make conversions from one currency to the other unless specifically noted.

For print titles, prices ranged from $7.90 to $43.24 in U.S. dollars. The total cost to get one of each is $3,492.09, at an average of $17.90 per title (195 available). This relatively low cost is due to library print jobbers offering substantial discounts, often more than 40%. To get a true cost, processing costs (whether done in-house by libraries or made shelf-ready by the jobber) and shipping costs (some libraries may have enough volume to not have shipping costs charged) should be added. These costs are not high. We are confident that total costs per volume in print for the U.S. are less than $20. However, it should be noted that in our initial study with 2018 data, U.S. library print books cost on average only $11.04. Since we are not looking at the same titles, we cannot make an absolutely valid comparison, but print costs for U.S. libraries seem to have increased greatly in 6 years, no doubt in part due to supply chain increases.

Prices ranged from $8.67 to $45.50 in Canadian dollars. The total cost to get one copy of each is $3,684.51, at an average of $18.80 for the 196 titles available. Again, adding processing and shipping, the cost per title should be less than $21 Canadian. At the time of this writing, the U.S. to Canadian exchange rate is $1 U.S. for $1.43 Canadian. The expected cost for each Canadian volume might be anticipated to be higher, perhaps as much as $26.88. For whatever reason, Canadian libraries get books at more of a bargain, much to the advantage of Canadian library readers. We’ll see if Canadian libraries benefit equally in digital. Interestingly, in our previous study, the average print cost per title was $20.39, not including shipping and processing. For the present set of mostly well-known and popular books, Canadian library costs per title are less than they were 6 years ago. This difference may be an anomaly: Many of the international titles from the previous study were available in Canada (and not the U.S.), but at a high cost. It is unlikely there has been an actual decrease in costs over 6 years.

|

General Conclusions on Licensing Trends

- Compared to our prior study, when the U.S. had 34% of titles available perpetually and Canada had 29%, the trend in ebook licensing is unfortunate. For the titles in this study—and the titles in both studies are generally comparable in age, with this study having titles even more likely to be collected—U.S. perpetual availability is down 15%, and Canadian is down 14%. This difference matters to libraries. With metered licensing, we must acquire the same title over and over to maintain access. It could be argued that many titles do not hold their interest over time. Library collections should not, however, be revolving platters with only the most currently popular titles, especially when it comes to significant lasting works. This trend greatly diminishes our ability to sustain collections over time. The impact on cost, as we shall investigate, is significant.

- The main source of the decline in ebook perpetual licensing is the Big Five. Smaller publishers are more likely to offer perpetual licenses than the Big Five.

- In audiobooks, three of the Big Five still offer a perpetual license; long-term access is thus more likely, but we must wonder if perpetual actually guarantees that libraries will be able to keep the books long-term if a publisher somehow loses the rights or, more likely, simply decides not to offer the titles at all anymore. We are concerned, however, that the Big Five will drop the perpetual-access option eventually, just as they all have for ebooks.

- If we must have metered options, licensing by number of circulations is preferable to time-bound exploding licenses. With circulation-based licenses, we have some likelihood of a return on what can be a considerable expense. The Big Five move away from perpetual to timemetered licenses since our last study greatly disadvantages libraries.

- A few titles are available in digital that are not available in print, due to print runs ending and print on demand not being available for them. Digital might offer some hope for long-term availability. Such hope, alas, seems illusory. Publishers are likely to drop such licenses if they are no longer perceived to have commercial value, even if the titles would then be forever lost. Publishers attempting to force the Internet Archive to close its Open Library shows how little interest they have in library preservation, even for books that have no commercial digital license. Nevertheless, if a library has acquired a perpetual-access license and the vendor and publishers do not somehow lose that access, there is some chance of maintaining long-term access even if print copies are no longer for sale.

|

Ebook Costs

For ebooks, total costs for a one-time acquisition of all available titles requires using more than one vendor. We have chosen from the various common models offered in a way that would suit a one-time acquisition: perpetual whenever possible, 26 circulations when only that option is offered, and otherwise metered by 2 years and not by 1. (The 1-year option is useful for meeting immediate demand; however, we would choose 2 years rather than renewing at 1 year for these titles to avoid the extra bother.) Getting the best price requires looking across all vendors, for there is more variation among vendors here than in title availability or licensing terms. In the U.S., there are 29 variances across the four vendors. There are 39 variances among the three vendors in Canada. Many are small, often less than a dollar. Others are significant. For example, Vendor 1 charges $23.99 for a title that Vendor 2 charges $56.57; on another, Vendor 2 charges $24, while Vendor 1 charges $86. Some of these differences seem due to sales—the vendors don’t have to charge what the publishers ask—but others seem to result from licenses originating at different times, with late-coming Vendor 3 offering lower prices in many instances.

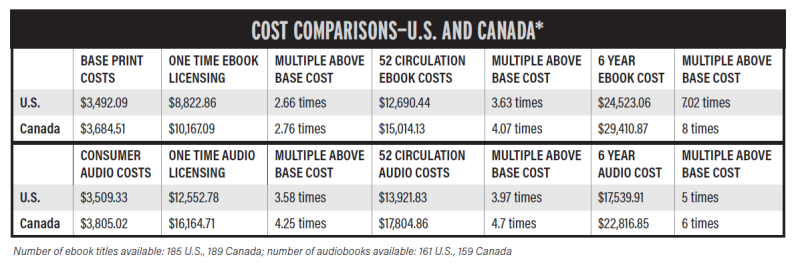

For the U.S., the total cost is $8,822.86, or $47.69 per title, and 2.66 times the cost of print (see the table on page 18). The comparison with print is even less favorable if we factor access over time. A circulation period for print and digital in our member libraries is 3 weeks. Digital circulation allows for faster return, but we cannot count on early returns. In any case, a frequent visitor might also return print more quickly than the full loan period. Even in the unlikely event that one of these books checks out again as soon as it is returned, 52 circulations would take 156 weeks, or 3 years at the same basic cost. For ebooks, we need to double the cost of items circulating 26 times by licensing, add half again for 2-year loans, and keep perpetual loans stable at their lowest cost among all vendors. That overall cost is $12,690.44.

Ebooks are now 3.63 times as expensive as print. Again, this is a conservative number when all factors for print (damage, wearing out, etc.) are considered. To compare with the 6-year average longevity to match one result we have seen, it is necessary to keep perpetual costs the same and double the other numbers yet again. The result is $24,523.06, with ebooks being seven times as expensive as print. Would most libraries wish to keep all of these books over 6 years, renewing them in digital if necessary? Would every title last in print without needing to be replaced for wear? Perhaps not. But many libraries might wish to keep all or most in print and digital. The scenario is possible, even likely, and not merely ideal.

For Canada, the one-time ebooks cost is $10,167.09, or $53.79 average per title, and 2.76 times the cost of the print titles. When compared to the U.S., Canadian ebook costs tend to be slightly higher on average than print. Just as with print, ebooks are still a relative bargain. The dollar exchange rate at the time of this writing would put Canadian ebooks at a whopping $76.17. Adjusting for ebooks for average print number of print circulations as we did for the U.S., Canadian ebooks will cost $15,014.13, or 4.07 times as much as print. Adjusting for the time print books might be on the shelf, the ebooks are $29,410.87, or eight times the cost of print.

Ebooks are not always more expensive than print. In the U.S., Vendor 3 offers some amazing deals. The Lost Bookshop by Evie Woods and The River Between Us by Liz Fenwick at the time of the study were available for $1.75 for 26 loans. Hellgoing by Lynn Coady costs $9.99 for perpetual access. Across all vendors, 20 perpetual-access titles are available from $7.99 to $21.99, often less than the cost of a print copy. These titles are all from smaller publishers. Not every small publisher/non-Big Five title is inexpensive. Sarah J. Maas’ House of Flame and Shadow—very popular at the time of the study—is $76 for perpetual access. It is more expensive than Big Five metered titles, but a better bargain than the many at $75 for only 2 years. U.S. costs range from $1.75 to $76. Librarians looking for cost-effective titles should look at smaller presses.

In the U.S., all 34 perpetual-access titles cost a total of $836.58 ($24.60 each). Not all are likely to be checked out often over the years; however, many are award winners and likely to be of lasting importance and interest. At very little more than the cost of a hardcover, they are a solid purchase. It seems that many small or even medium-sized publishers are not in ebooks for maximum profit, an attitude sadly lacking with the Big Five. As noted previously, the Big Five offer no perpetual-access titles in their own imprints. Their metered titles in the U.S. average $52.71 each and $58.22 in Canada ($59.56 and $64.58 if one excludes the less costly 1-year or 26-circulation titles)—many times print costs. Furthermore, and unfortunately, at least from the Big Five, libraries don’t get much of a price break on older titles. Of the 24 Big Five titles that are 10 years or older, all prize winners of some sort, only three in the U.S. cost less than if they were new; all of those seem to have kept the older (and more favorable) license terms from when they were published by a smaller publisher, now subsumed by the Big Five.

In Canada, a similar pattern exists. The price range is wider, from $1.75 (from Vendor 3 for a 26-circulation loan) to $139.99 for a 2-year loan on Doris Kearns Goodwin’s An Unfinished Love Story: A Personal History of the 1960s. Once again, smaller/indie/non-Big Five publishers offering perpetual access are the best deals. Twenty-one such titles can be had perpetually for $446.04, a mere $21.24 per title—about the same price as for print without having to reshelve or move between branches. The 28 total non-Big Five perpetual-access titles, even including the $104.96 for Maas’ book, can be acquired for $31.37 each. HarperCollins deserves a mention for offering three titles in the $21 range, though only for 26 circulations. Once again, older Big Five titles have no price reduction. Indeed, the oldest title—Norman Mailer’s 1979 The Executioner’s Song—costs $75 from one vendor and $86 from two others for a 2-year loan, making it a marginal purchase for all but the largest libraries and likely even for them.

If we assume 52 circulations as an average—again, we regard it as a conservative number for high-demand print—we can factor as cost-per-use, recognizing that a study of actual title use over a 6-year period would be ideal but impractical. For print, that cost would be 38 cents for the U.S. and 40 cents for Canada. For a one-time license of ebooks, it is 92 cents for the U.S. and $1.03 for Canada. The cost, alas, rises over time. For 52 circulations, the U.S. cost-per-use is $1.32, and the Canadian is $1.53. While higher than the print cost by many factors, these ebook prices seem like bargains compared to the cost of pay-per-use: often $1.49 to $2.99 or more. Ebooks on these do develop wait lines, often long ones. The wait can be discouraging for patrons, but that is a feature and not a bug for Big Five publishers. Having titles always available is nice; however, in a time when cost increases exceed budget increases, it is no surprise that many libraries are moving away from pay-per-use models since they are unsustainable in cost.

Two by-number-of-circulation metered models appear frequently enough to warrant separate attention: 26 circulations and 100 circulations per license. The 26-circulation option is available on 19 titles in the U.S. Vendor 4 discounts prices somewhat on four titles, so we’ll use its numbers and add the cost from the other vendors for one title it doesn’t carry. The total is $660.63 ($34.76 per title, or $1.34 for 26 circulations). In Canada, where more 26-circulation titles are available, 28 titles cost $862.31 ($30.80 per title, or $1.18 for 26 circulations). This license type—from HarperCollins and its imprints—is not a bargain when compared to the smaller presses, especially those that offer perpetual. It provides a fairer price than the other Big Five titles, but still greatly exceeds cost for print. HarperCollins and two other indies are offering the 100-circulations model to one vendor. Here, the title’s age is making a difference. The cost for 17 titles in the U.S. is $53.98 for older or midlist titles and $139 for newer titles and bestsellers. Total cost is $1,821.84 ($107.17 per title). The less-expensive titles are basically 54 cents per circulation and a bargain, especially since one can count on them for 100 circulations—about as close to perpetual in ebook licensing as any of the Big Five offer.

Keeping up with the demand for popular titles can, it should be noted, require considerable expense, even if less on average than some other license types. The more expensive titles are slightly higher in cost than the ebook average, but less on average than the other Big Five titles. Canadian prices, unfortunately, are not as favorable: 12 titles range from $74.55 to $233.40, with only two at the lowest amount. The average cost is $200.24, more than $2 per circulation. The lower range may offer good return, but the upper cost may not. Caveat emptor: In Canada, for example, Barbara Kingsolver’s Demon Copperhead is $191.97 for 100 circulations. Vendor 3 offers it for $35.36 for 26 circulations, which would be only $141.44 for 104 circulations. In the U.S., the same book is $139 for 100 circulations, but Vendor 1 offers it for $30.85 for 26 and thus $123.40 for 104 circulations. Perhaps not having to reorder four times at 16 makes the deal seem worthwhile. We thank HarperCollins for doing a bit better in some cases than some others. We encourage other large publishers and ebook vendors to work toward this model if we cannot leverage anything better. Still, costs greatly exceed print; varied models with some good deals compared to the competition cannot hide that fact.

Audiobook Costs

Unlike with print, digital audiobooks do not offer a good comparison with analog in libraries. Libraries used to get many books in audio on tape and then on disc; they were expensive and were frequently lost or damaged. For a time, a market in disc resurfacers thrived. Today, digital has gone past the disc, and many libraries no longer get audiobooks on disc or find that not all titles are sold to them in that format. For illustrative purposes only, we will compare library digital costs to consumer costs for the same titles and also see how audio compares to the standard ebook. In the U.S., the 161 library-vendor available titles total $3,509.33 ($21.79 each). In Canada, 161 titles add up to $3,805.02 ($23.63 each). Publishers would no doubt argue that library loans go to many people, so they would lose money if libraries licensed at this cost. This argument is difficult to credit when libraries get print books at far less than consumer costs, buy many more copies in print than they license in digital, and have helped sustain publishers at these terms for years. We are not arguing that libraries should get consumer costs; the Big Five, as we shall see, license under prices that are far inflated above the print equivalent.

In the U.S., the audio titles are available one time for $12,552.78 ($77.97 each). We count the perpetual option for the Penguin Random House titles rather than the 1 year at half-price option—the latter being cost-effective only to fill high short-term demand. That amount is 3.6 times the consumer price. Cost variations across vendors are small compared to ebooks, with only seven prices being different. All of those differences are at least $12 per title, with all vendors offering at least one bargain. Comparing the increase in cost for 52 circulations or 6 years’ worth of costs is more favorable for library budgets than with e-books because of the far greater perpetual access available. The 52-circulation number is $13,921.83, which is an increase of $1,369.05, or 3.97 times the consumer price. Over 6 years, the cost is $17,539.91, or $4,987.13 more than the initial cost of $12,552.78 and five times the consumer cost. Compared to ebooks, the initial costs are higher but become more and more a relative bargain over time.

This is not to say that digital audio is low cost. Demon Copperhead is available for perpetual access at $137.22. While its cost per use will decrease over time, its 52-circulation cost is $2.64. The Executioner’s Song is metered access for $124.99, with a 52-circulation cost of $187.49, or $3.61 per use. At that price, few would take a chance on it circulating well enough to earn its place. The high cost of digital audio—particularly for older works—may mean not acquiring any but the most high-demand titles. The Big Five are the big offenders, charging an average of $77.39 per title versus $21.17 by the independents.

Costs Summary

- Ebooks greatly exceed print in costs, not only initially but exponentially over time.

- Ebooks are even more expensive than 5 years ago, with the initial costs for licensing one of each available title in the U.S. being $47.69 and $53.79 in Canada, compared to $35.54 and $37.62 for comparable titles then. The less expensive indie titles do not offset a larger price increase by the Big Five.

- Digital audiobooks are initially more expensive than ebooks; however, due to the higher number of perpetual licenses, they do not escalate as quickly. It is debatable, though, if the remaining members of the Big Five will keep the perpetual option.

- High initial license costs, especially on timebound licenses, make many digital titles marginal. Most libraries can’t afford to spend the average $60–$65 for time-bound metered books without having some likelihood of high circulation. The high cost of having to retain these books more than 2 years makes many titles even more likely to go uncollected.

- Varied license terms are welcome and can, in some cases, lower costs; however, alone, they seldom guarantee anything approaching print equivalent prices.

- Medium, smaller, and indie publishers are more likely to offer lower costs—sometimes even lower than print—with better overall licensing

terms.

|

In Canada, unlike in the U.S., many variations in cost occur across the three vendors. Here, Vendor 2 comes into its own, not only offering more titles but beating the others on price 90 times on the 161 available titles. In many instances, the savings are only $1–$3, but the difference is substantial: $47.30 saved on one perpetual license and $112.10 on another. This vendor falls down rather badly by only offering the 1-year and not both 1-year and perpetual licenses on Penguin Random House and imprints titles. Vendor 3 had just entered the market the month of our data collection; not surprisingly, it offers fewer titles but shows promise by offering the lowest cost in some instances and carrying titles the others do not. Overall costs across vendors range from $3.99 to $194.93, with the one-time licensing at $16,164.71, at an average of $100.46 per title. This is 4.2 times the average consumer title price of $23.82. The Big Five costs average $104.48, and the other publishers only $81.83. The 52-circulation cost is $17,804.86, and the 6-year cost is $22,816.85. The high percentage of perpetual titles helps keep long-term costs less than they otherwise would be. As with the U.S., however, some titles push the limit of sustainability. Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch lists at $160.76 from the least expensive vendor. The 52-circulation cost is $241.14 ($4.64 a circulation). The 6-year cost is $482.28, which is 20.2 times the average consumer cost. Demon Copperhead is available on perpetual license for $173.82; 52 circulations would cost $3.34 each, which is substantial even if the license would average less over time if held for 6 years and still circulating regularly.

Vendor 1 carries 43 audiobooks in the 100-circulation model in the U.S. and 39 in Canada. U.S. costs range from $32.92 to $219. In Canada, costs range from $32.95 to $296.23. The lower end of the scale creates costs per use that nearly match those of print, an undoubted bargain. At the higher end, Anne Boyer’s The Undying: Pain, Vulnerability, Mortality, Medicine, Art, Time, Dreams, Data, Exhaustion, Cancer, and Care would cost $2.19 per circulation, but a perpetual-access copy can be licensed for a mere $65. In Canada, Demon Copperhead will cost $2.96 for every circulation, but perpetual can be licensed for $173.99—that’s hardly a bargain but likely to be far more cost-effective over time. If the 100-circulation model allowed for simultaneous access, it may at some prices be an efficient way to address long waiting lists. In other cases, it looks like a bad deal.

A Brief Vendor Comparison

Our aim in this article has not been to compare the various ebook vendors but to consider the market as a whole. This aim has meant looking across all vendors for availability and the best license terms. Few, if any, libraries will have the requisite personnel to look at all of these vendors to do the same. Tracking titles across different platforms could give greater ROI, but the savings would be eaten up by staff time. Even if some system were to automate across all vendors, the library would face the problem of directing patrons to different places—not a good option. One of ReadersFirst’s basic tenets—rightly so—is that all titles should be available in one place.

Our study does allow a few general conclusions to be made about the vendors. Vendor 1, the industry leader, has the greatest availability of titles; it sometimes has sales and is generally competitive on price. Its 100-circulation model offers some relative bargains. The other vendors might wish to negotiate for this model. Vendor 2 has the greatest availability and often the best prices on audiobooks, especially in Canada, but its failure to offer the 2-year option and the perpetual audio option on Penguin Random House books hampers it. Vendor 4 has apparently not expanded the model we tested in Canada, or we could not find a Canadian library that used it. It is better known for its pay-for-use model. Many libraries are finding that model unsustainable, with costs constantly rising. They must either cut back on the number of checkouts per user or suppress higher-cost items—likely both.

The newest titles are also not available as pay per use. The more traditional models we have studied here could assist. They often are a bit less expensive than with Vendor 1. Many popular titles would no longer be always available and would develop waiting periods, and costs would be contained while lesser-known works might always be available. This vendor has some quality issues on these lesser-known works. We recommend caution in surfacing them, but patrons of well-funded libraries might at last have a way to discover what libraries might not collect due to onerous license terms. Vendor 3 is newer than the others—it’s new in Canada. Especially there, title availability is less. It has two major advantages. First, it has exclusive access to desirable titles. Second, it will display titles that a library may have licensed from Vendors 1 and 2, being a one-stop shop for content. Being newer, it has negotiated some lower license costs than the others. It can be adopted inexpensively; one can get titles from it as it arranges for more content. It’s been proactive about developing new license models, including actual ownership of digital content.

Conclusions

Six years later, our follow-up study identifies some positive trends. The availability of award-winning and bestselling digital titles is, if anything, even greater than before in ebooks. Enormous gaps in what is available in digital before 1980 no doubt still exist, but the majority of books that public libraries wish to collect on an ongoing basis for adults should be on hand. It would be valuable to do a study of teen and children’s books. Digital audiobooks are less likely than ebooks to be available through our vendors, especially if they are older. Since they are more readily available to individual consumers, we should encourage vendors to make more available to libraries. This, however, may require more licensing through a company such as Audible. While Vendor 3 has started this process, progress may be difficult. More license options exist than 6 years ago, and many of them can help libraries make better use of their limited funds.

Vendor 3 developing ownership models with independent publishers at very reasonable prices will help, even if the Big Five remain unlikely to buy in. A study including owned titles and those from Amazon or Audible would be informative. The present study makes one thing clear: Medium-sized independent publishers are often giving us much more fair terms than the Big Five. If we are to have broad, deep, and sustainable digital collections, advocacy for fair prices and new licensing models is of paramount—and ongoing—importance, while short-term refocusing of what we acquire while becoming tastemakers to create demand for often neglected non-Big Five content is recommended. For a full discussion of conclusions and recommendations, see the ReadersFirst website: readersfirst.org/news/2025/7/1/some-unpublished-parts-of-the-cil-article.

We of the ReadersFirst Working Group in the U.S. and Canada are pleased and proud to have collaborated on data collection and evaluation. We pledge to work together for mutual support of libraries and increased access to digital content in both the U.S. and Canada, especially during one administration’s mistaken efforts to break our two countries’ friendship. Together, we are as strong distinct countries dedicated to the best for our millions of readers.

|