Shfiting Gears: Is AI Flipping Jobs or Safety?

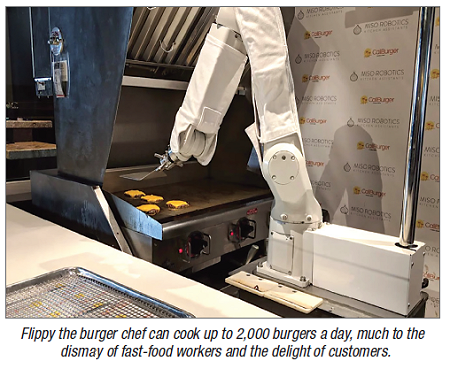

Automation is a major challenge to our contemporary economy. These days, fast food self-order kiosks, self-checkout at grocery stores, and even online retailers are fierce competitors for individuals seeking employment. In March 2018, Caliburger, a burger joint in Pasadena, Calif., decided to invest in a robot that flips up to 2,000 burgers a day. Caliburger introduced the robotic burger chef named Flippy to combat high part-time employee turnover rates at the restaurant (“A Robot Is Now Flipping Fast Food Burgers, Is This the End to the Short Order Cook?” Jefferson Graham, March 5, 2018; usatoday.com/story/tech/talkingtech/2018/03/05/flippy-robot-now-cooking-up-burgers-near-l/390179002). This is an unsettling move today, when the fight for a living wage across many service sector and manual labor jobs is raging. Automation could lead to an elim ination of these types of jobs instead of companies paying employees a living wage.

A widely discussed recent development in automation is self-driving cars. In the last decade, many major car manufacturers around the world have produced cars capable of some kind of autonomous driving. Many companies are also projected to launch their own lines of completely self-autonomous cars by as early as 2020 (“Here’s When Having a Self-Driving Car Will Be a Normal Thing,” Gene Munster, Sept. 13, 2017; fortune.com/2017/09/13/gm-cruise-self-driving-driverless-autonomous-cars). At the beginning of 2018, ride-sharing service Uber boasted that it would offer driverless cars throughout the county in 18 months or less, and as a result, some states even gave Uber the opportunity to test-drive on their streets. On March 18, 2018, in Arizona (a state that approved Uber to test self-driving cars), an autonomous Uber vehicle struck and killed a pedestrian after its lidar (light detection and ranging) sensors failed to identify a pedestrian crossing the street 100 feet away. Almost immediately after the accident, Uber suspended its self-driving car tests around the country (“How a Self-Driving Uber Killed a Pedestrian in Arizona,” Troy Griggs and Daisuke Wakabayashi, March 21, 2018; nytimes.com/interactive/2018/03/20/us/self-driving-uber-pedestrian-killed.html).

Self-driving cars operate through a computer, preloaded maps, radar, and sensors installed in the car. Information during the drive is sent to AI software that plots a route using advanced algorithms that enable object differentiation; rules to be followed, such as speed limits; and the navigation of different obstacles on the road. Often, autonomous models will be partially self-operated, so that the driver must intervene at some point during the trip. Prior to this accident, we were all envisioning a world where driving is no longer a rite of passage and these transportation service jobs were the labors of a bygone era. However, few of us would trust self-driving cars if they cannot avoid hitting pedestrians, something most human drivers do not do while behind the wheel. After this failure of its system, Uber has a lot of work ahead of it instill consumers with confidence in relying on autonomous cars. While self-driving cars might be a staple of normal life one day, it is definitely not a feature of the year 2020. There are too many bugs to work out in the technology and too much work to be done on the companies’ end before trust can be regained within the general public. We are not emo tionally ready to give up our keys to a computer program. Grocery checkout lines, ATMs, and fast-food restaurants will have to suffice for now.