Scholarly research, particularly in the sciences, has changed. As content goes digital and researchers embrace nearly instantaneous full-text and sharing capabilities, publishers have scrambled to control distribution, facilitate copyright-compliant sharing, and respond to the researcher’s quest for digital research management tools.

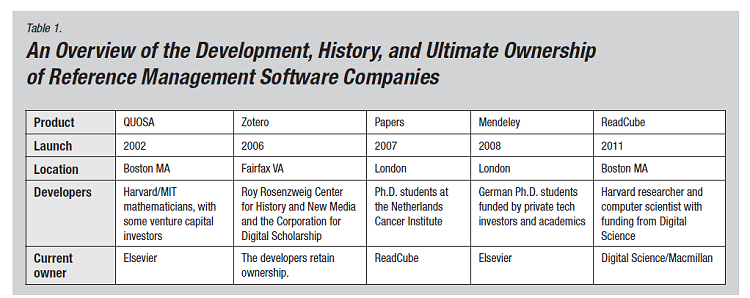

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, creative souls in Europe and North America sought to develop the kind of reference management tools that would meet these needs. QUOSA was one of the earliest, followed by Zotero, Papers, Mendeley, and ReadCube. These tools, with the exception of Zotero, which remains a free, open source project of the Roy Rosenzweig Media Center for History and New Media, have become part of a panoply of publishers’ products.

The trend started in 2012, when Elsevier announced that it had acquired QUOSA, self-described as a “provider of life sciences content management and work flow productivity solutions.” In a Jan. 23, 2012, NewsBreak (newsbreaks.infotoday.com/NewsBreaks/Elsevier-Acquires-QUOSA-What- Does-This-Mean-80126.asp), I wondered what this would mean for researchers. What would Elsevier do with QUOSA? In looking at the bigger picture, 3 years on, we might also ponder what this might have meant to other publishers and content creators. (See the Overview table below.)

Developers and founders created reference management tools for scholars seeking to manage published literature for research purposes. This environment fosters the need for the sharing of findings, quick access to full text, and tracking of research work to understand what has been published when and by whom. Once these products reached a reasonable level of development, founders moved to sell or partner with larger companies. Elsevier bought QUOSA and Mendeley, while Springer bought Papers.

ReadCube is a slightly different case in that it grew up within the realm of publisher Macmillan. At its inception, ReadCube served Nature Publishing and Frontiers (Macmillan companies), but also John Wiley. This landscape shifted in January 2015, when Macmillan and Springer announced their intention to merge and, in May 2015, became Springer Nature. A key scientific publisher missing from this reference manager tool equation is Wolters Kluwer. In 2005, it partnered with QUOSA for Ovid users, but that partnership ended in 2011.

What has happened since Elsevier bought QUOSA and Mendeley? What is Elsevier’s strategy with QUOSA, and what has it done to move in that direction? Where does Mendeley figure in? What is Wolters Kluwer doing to offer reference management tools to their subscribers, and what will the Springer/Macmillan merger mean for ReadCube?

Tune in next month … no, not really. Although these areas are always moving targets, evolving even as you read this, we can take a snapshot in time and see how things stand today. Then we’ll look at where things might be going.

BIOMEDICINE AND SCIENTIFIC PUBLISHING

It is no coincidence that much of this activity revolves around biomedicine and scientific publishing. Academic and commercial researchers in pharmaceuticals, diagnostics, medical devices, and related biotechnology industries rely heavily on the literature to guide their work. Text mining, literature searching, literature sharing, and reference management inform and advance research and development.

Government regulations require these functions. Devel oping lifesaving and life-sustaining products in the biomedical arena resembles adding layers to a pearl. First, here is a molecule, a compound, a device, or an idea representing the grain of sand at the center of a pearl. Layers of information, typically documented in the published literature, develop that grain of sand into a product that is proven to have some efficacy or to solve a healthcare problem. This product is eventually approved by the various national regulatory bodies for sale and distribution. Research reports, peer-reviewed publications, and regulatory submissions add layer upon layer to the knowledge around that grain of sand, increas ing its value and applicability. Thus, tracking and sharing all of the information that constitutes these layers become an essential part of the development process, the regulatory processes, and the necessary safety monitoring that follows a product launch.

Elsevier recognizes this. Part of its corporate strategy is to advance research through information technology. Elsevier’s content centers on life sciences, and the company is acquir ing and developing technology to promote content. CEO Ron Mobed, interviewed in March 2014 (thebookseller.com/feature/ron-mobed-interview), said this:

This is a content business: the acquisition and production of content, the curation of the content, the dissemination of content. In the past 20 years, Elsevier has been at the forefront of technological advances, and we need to be, because that’s what researchers and practitioners need: more useful ways to access, analyse and search content. If I’m the steward of anything, it is managing that combination of tech and content.

QUOSA is the technological solution Elsevier offers the drug industry. It targets medical affairs, which respond to customer inquiries, and pharmacovigilance, which moni tors product safety. In fact, when I contacted a QUOSA sales representative on Aug. 7, 2014, to inquire about us ing QUOSA for knowledge management in a small chemical institute, I was encouraged to look elsewhere. He said, “QUOSA is generally sold to large pharma for pharmacovigilance” with the intention of leveraging the life science portfolio found in the Embase database. He further noted that QUOSA already had 20–30 customers in the U.K. Press releases, news reports, and the QUOSA website indicate that Sanofi (France), Celgene (United States), and Shire Pharmaceuticals (Ireland) have adopted QUOSA. The U.S. National Institutes of Health, along with numerous universities, can also be identified as a user.

With Elsevier owning both QUOSA and Mendeley, it’s important to differentiate them. And they are different. QUOSA is a subscription service intended for enterprise-wide application, while Mendeley is free to individual users. It offers a referencing platform with social media features. Mendeley has an institutional edition targeting academic environments; the product had more than 2.5 million registered users when Elsevier bought it. By spring 2014, it had surpassed 2.5 million, and, according to Mobed, numbers are “strong and on target.”

Thus Elsevier appears to be racking up academic researchers with the free Mendeley tool while targeting the high-value biomedical industry with QUOSA.

SPRINGER NATURE

In 2012, Springer Science+Business Media bought Papers, a contemporary of QUOSA. Just a year before that, Macmillan rolled out ReadCube after funding its development through its Digital Science subsidiary. In January 2015, the respective owners of these two publishing giants announced a merger. All of Springer Science+Business would merge with parts of Macmillan ( Nature, Scientific American, Palgrave Macmil lian, and Macmillan Education). Digital Science, and thus ReadCube, was not part of the deal. (Marydee Ojala provides the details in a Jan. 27, 2015, Newsbreak: newsbreaks.infotoday.com/NewsBreaks/Springer-and-Macmillan-Poised-to-Merge-101703.asp). We can see the outcome of this merger process. You might want to top off your coffee and get comfortable. It’s complicated.

The new company is called Springer Nature. Springer brought Papers to the table while Digital Science retains ReadCube outside of the Springer Nature brand. Springer promoted Papers, emphasizing workflow management and targeting the general research and academic community for both individuals and teams. According to the website, Papers is in use at the University of Cambridge, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), and Stanford. Note: Mendeley also claims users at MIT and Stanford. (Now would be a good time to take a sip of coffee.)

In July 2015, Springer Nature announced a partnership with ReadCube Discover to enhance findability of its content, stating, “more than eight million scientific documents on Spring erLink have been indexed by ReadCube’s Discover service.” Furthermore, “[a]ll Springer journal articles, book chapters and proceedings viewed within the ReadCube environment now feature enhancements such as hyperlinked inline citations, annotation tools, clickable author names, integrated altmetrics and direct access to supplemental content.” Springer Nature has set up an example of one of these interactive articles at rdcu.be/c0Mt. It appears, therefore, that it’s Papers for the masses and ReadCube for the scientific community.

These endeavors, however, were merely a prelude to an acquisition. ReadCube announced on March 16, 2016, its purchase of Papers from Springer Nature for an undisclosed sum.

On the Nature side of the equation, we find that Nature has leveraged ReadCube in interesting ways. In December 2014 Nature announced a 12-month content-sharing initiative to support collaborative research. During the trial, subscribers were allowed to share the content of 49 journals with non-subscribing colleagues via a web link enabled by ReadCube. “The trial had no adverse implications for subscription-based journals either in terms of institutional business or individual article sales” (nature.com/press_releases/npg-readcube-trial-results.html).

Since ReadCube still belongs to Digital Science (not Springer or Nature), there is the opportunity to partner with other publishers, and it appears the practice is widespread. Digital Science has partnered with more than 65 publishers, including Wiley (which uses ReadCube Connect), Karger, De Gruyter, MIT Press, JAMA, Emerald, New England Journal of Medicine, Brill, Project MUSE, and, interestingly, Elsevier. ReadCube claims more than 15.3 million users and more than 40 million articles available as enhanced PDFs. Perhaps if Elsevier’s QUOSA is the iOS of management tools, ReadCube is the Android.

Wolters Kluwer

After a 6-year relationship with QUOSA, Wolters Kluwer’s Ovid unit declined in 2011 to renew its contract. It appears that the Ovid team has not opted to compete with Elsevier in the reference management department. As the deadline for this article neared, I received word from the Wolters Kluwer corporate communications department that Ovid offers a built-in reference management tool called My Projects that facilitates organizing and sharing references collected from Ovid. In researching My Projects, I found the Ovid Toolbar Download that lets users collect and manage research from other online sources. However, according to the Ovid spokesperson, “It is very common for our users to run a search and then export the references into an external tool for management/consumption.” It’s probably not too much of a stretch to assume that Mendeley is one of those external tools. Furthermore, according to the ReadCube publishers, Wolters Kluwer Health is one of its publisher partners, having teamed up in 2014. It is unclear how it is using ReadCube.

Are we there yet?

Going back to the January 2012 NewsBreak discussing Elsevier’s acquisition of QUOSA, I again ask what this means. Elsevier has jumped into the deep end with a reference management/sharing tool positioned to meet a specific need for the biomedical industry, most specifically, the pharmaceutical segment. With Mendeley, it has cornered the freebie market for individual science researchers. ReadCube’s Papers offers an alternative to Mendeley, but Papers does not seem to have the momentum or the traction seen at Mendeley. This may, of course, change with new ownership. If hiring is any indicator of growth, Papers is growing slowly at this point, with only one job opening listed on its website, while Mendeley has nine.

While Elsevier targets pharmaceuticals with QUOSA and sciences in general with Mendeley, ReadCube is reaching out broadly to science publishers, leaving the rest of the market for Papers.

Perhaps we’ll have to take another look in a few years to see how things continue to unfold.