If you, like me, are thinking about the future of our planet, you will likely have a myriad of thoughts about the countless issues we face today—rising temperatures, water scarcity, and global health pandemics, to name just a few. These issues represent the challenges of human sustainability—our need to look beyond the here and now and ensure a future for generations to come. While the many different areas of human activity require dedicated and specific efforts to ensure a sustainable future, you can argue that underlying it all is the need for unfettered access to trustworthy information and the relentless acquisition and creation of knowledge. [This is embodied in the United Nations’ Sustainability Development Goals (un.org/sustainabledevelopment), particularly SDG #16. — Ed . ]

This is where libraries have historically played an essential role; libraries have served as conduits for the collection and dissemination of our cultural heritage and scientific advances. Yet arguably today, the very relevance—and, indeed, sustainability—of our library services are gradually becoming more dependent on our ability to adapt to an increasingly connected technological landscape. To truly meet the sustainability challenge, therefore, and support our users’ current and future needs, we must rethink the tools we deploy and the services that we—as libraries and vendors—provide to our constituents. It is in this context that we must make the case for “open” in libraries.

|

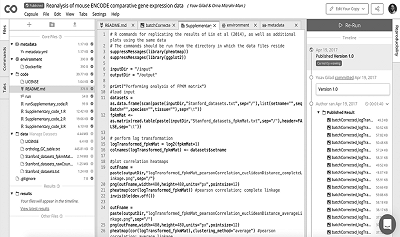

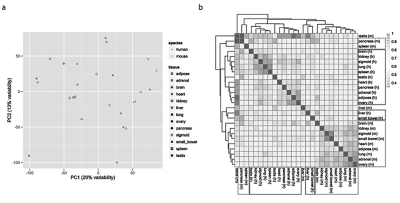

Graphs from a F1000 article illustrate the analysis but do not provide insight into underlying code and data or the exact computational environment used.

(Click for full-size image) |

|

A Code Ocean compute capsule gives the research community access to an executable instance of the analysis.

(Click for full-size image) |

Open in Support of Research

Before proceeding, a common understanding of what we mean by “open” is necessary. In essence, “open” seeks to remove barriers across the technology and information ecosystem. In the case of software or systems, “open” seeks to clear hurdles for the provisioning, developing, extending, or enhancing of the solution at hand. For information, “open” means ensuring optimal, unbiased, or unrestrained access to content. This includes but is not limited to data, code, methods, articles, and books. “Open” implies a connected infra structure in which disparate solutions interoperate to deliver best-of-breed services to users.

Looking at the activities and tools involved in open re search workflows, Bianca Kramer and Jeroen Bosman at the Utrecht University Library in the Netherlands focused on research creation, sharing, and processing with their Innovations in Scholarly Communication project (101innovations.wordpress.com). These activities consist of preparation, discovery, analysis, writing, publication, outreach, and assessment. Across these tasks, the available tools number in the hundreds, and researchers have a multitude of ways to ensure their research and workflows are, indeed, open. In this article, I hone in on systems and tools and consider the importance of “open” across two areas in particular—the creation of and access to the various components that comprise the research, plus the infrastructure and systems that libraries deploy to collect, manage, disseminate, and preserve the overall research output.

Research Discovery

The beginning stages of research are characterized by ideation and discovery. Typically, researchers at this point will consult an abundance of tools, including the library’s discovery service, to unearth articles in their discipline and comb through peer-reviewed literature. The challenge is to deliver to researchers the most relevant results for their discipline. Success here is primarily dependent on the indexing of the content and the search algorithms. For example, if a discovery service properly leverages subject indexes, which contain highly detailed thesauri and controlled vocabularies, researchers will not miss out on important results for their query.

Additionally, and certainly for ensuring discoverability of open access articles, any biases in the search algorithm must be accounted for. Bias may be introduced by favoring certain types of content over others (for example, content with greater frequency of publication, such as newspapers or trade periodicals) or by allowing commercial interests or affiliations to skew results. The discovery service vendor, therefore, should openly disclose the “recipe” and share the inner workings of its search technology to remove any mystery for researchers and content providers.