Patent database producers and their users continue to be challenged by the ever-increasing number of patent documents in a multitude of languages with various types of non-textual content. Increasingly sophisticated tools allow patent searchers to navigate the world’s collection of patent documents and to be more efficient throughout the search process—from receipt of a search request to delivery of a final search report.

Professional patent searchers, in particular, have made gains from improvements in enhanced patent search systems from commercial sources. These improvements go well beyond what free patent databases offer and provide viable alternatives to expensive, value-added patent databases that index patent content .

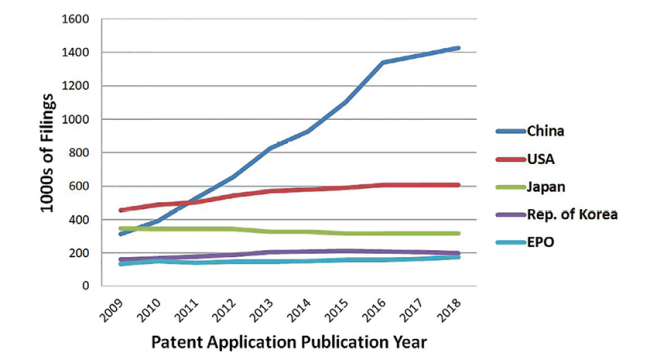

A regular concern for database producers and profession al searchers, expressed at technology conferences and in patent blogs, is the vastly increasing numbers of patent applications filed worldwide in many languages. Patent filings for the top five patent offices within the past decade, including filings made under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), show an enormous increase in filings from China, according to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) Statistics Data Center (wipo.int/ipstats). Plus, these filings could be made in any of three Asian languages (Chinese, Japanese, or Korean) or the three official European Patent Office (EPO) languages (English, French, and German). There are four additional official publication languages for PCT filings: Arabic, Portuguese, Russian, and Spanish.

In fact, the EPO and the WIPO International Bureau as receiving offices (wipo.int/pct/en/filing/filing.html) accept patent applications in almost any language as long as they are translated into one of the 10 official languages. Other patent offices take applications in their home languages without requiring translation into other languages.

|

| Patent filings for the top five patent offices across the past decade, including filings made under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), showing the huge increase in filings from China. |

Patent Databases and Search Systems

The most economical way to deal with large patent datasets is to use automated processes for gathering and organizing patent information from sources worldwide. These processes scale up well as computing resources become faster and cheaper. The simplest patent search systems that facilitate access to the worldwide patent databases are produced by patent offices, search engine providers, and other organizations that choose to offer free access and limited search and output functionality. Examples include Google Patents (patents.google.com), Espacenet (worldwide.espacenet.com), and FreePatentsOnline.com. These free patent search systems are excellent resources for inventors, researchers, managers, and even patent agents and attorneys who do not need to carry out comprehensive searches to support legal or other high-stakes decisions.

Professional patent searchers, their employers, and clients rely on commercial patent search systems that offer many advanced features and facilitate efficient and effective patent searching. These enhanced patent search systems are supported by subscriptions and include Derwent Innovation (Clarivate Analytics), Orbit Intelligence (Questel), and PatBase (Minesoft). These enhanced patent search systems are the focus of this article.

Many patent searchers, scientists, engineers, and attorneys continue to use older, value-added patent databases such as Chemical Abstracts’ CAplus, Derwent World Patents Index, and EnCompass (formerly American Petroleum Institute) Patent Database. Other former favorites, such as the US CLAIMS database, are defunct. Producers of these value-added databases are particularly challenged by the increasing number of patents. They employ technical experts to index and abstract individual patents and applications and, in some cases, non-patent literature as well. However, these human efforts do not scale well, although they can be supplemented by computer-aided processes. Many users have dropped subscriptions to the value-added databases due to their relatively high subscription costs; the availability of non-subscriber, transactional access to much of the content; and the competitiveness of enhanced patent search systems.

How has this shift affected the ability of professional patent searchers to carry out effective patentability, invalidity, and freedom-to-operate (FTO) searches? What are the factors that affect the productivity of individual patent searchers like me? What conclusions can be drawn about how these trends have affected patent search quality?

Search Productivity and Unit Cost Improvements

My personal productivity, measured in the number of search reports that I can produce in a week, month, or year, has in creased, even while the amount of patent data that I search and review has grown. Correspondingly, the average amount of time that I spend on each search project, from request intake and client interview to issuing the final report, has decreased significantly.

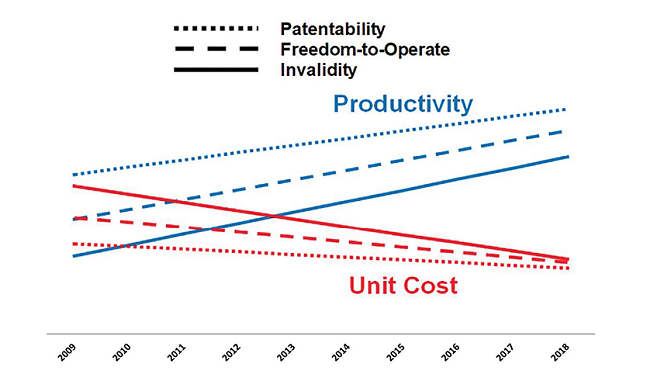

To confirm this, I analyzed the amount of time per search (unit cost per search) and productivity (efficiency corresponding to searches per unit time) for my work during the past decade. I graphed my unit cost data and productivity (smoothed by linear regression) for patentability, invalidity, and FTO search reports. The slopes of the search data are intended to be representative of the actual data, but the y-intercepts are absent in order to maintain business confidentiality. These results correspond to 25–50% reductions in unit costs, leading to productivity improvements of 50–100% across the past decade. Improvements in unit cost and productivity were significantly greater for invalidity and FTO searching than for patentability searching.

|

| A graph of my unit cost data and productivity (smoothed by linear regression) for patentability, invalidity, and FTO search reports. |

Searcher Experience and Search Technology

Searchers gain proficiency across time with search tools and resources and with their clients’ technologies. However, repeat work from loyal clients on technologies that match my expertise cannot account for more than a modest portion of the reduction in unit costs of my searches of the past decade. The most significant changes in my personal growth took place more than 10 years ago when I started to document my processes on invalidity and FTO searching [1, 2, 3].

Most of the reduction in cost for my search services across time is attributable to technology improvements in the search tools I use. To remain competitive, vendors naturally make changes to improve their search products and develop new functionality that takes advantage of new computing technology.

These improvements affect various types of searches in proportion to how labor-intensive they are. In general, FTO and invalidity searches are more labor-intensive than patentability searches because they involve detailed consideration of large numbers of patent documents. FTO searching involves review of claims of granted patents and pending patent applications in the countries or regions of interest to the client. The cost of such searches is mitigated somewhat because FTO searching is restricted to patent documents applied for within the past 20 or so years, corresponding to potential enforceability.

Invalidity searching is more intense than patentability searching because the searcher must scour patent specifications (and literature articles, especially when readily available and reasonably priced in full text) to find disclosure of matters claimed by the patent that is the target of the invalidity search. The cost of invalidity searching may be lessened for older target patents because the search covers patents and non-patent literature that were filed or published before the filing date of the target patent document. In these cases, searchers can help attorneys evaluate results of invalidity and FTO searches by pointing out specific claims, specification text, or both in the search reports. In contrast, patentability searches are less rigorous and require less labor to review prior art and report findings. They are usually early-round novelty searches of proposed inventions. The potential penalty to the client of unreported prior art is less compared to invalidity and FTO matters.

Value-added Databases

Advances in enhanced patent search systems have revolutionized how patent searchers work. Enhanced patent search systems allow for a start-to-finish search process. Searchers can cycle through search, retrieve, review, learn, revise strategy, and repeat easily and repeatedly. They can review candidate references in detail during the course of the search, which has the biggest impact on FTO and invalidity searching.

Searchers no longer need to rely on value-added databases, except in some specific technology areas, to find manageable sets of patent documents or patent families for further personal review and evaluation by researchers and patent attorneys or agents. There is no need to order patent documents separately and interrupt the search process. In effect, the searcher becomes the real-time expert and diminishes the need to outsource to other technical experts to read, interpret, abstract, and index original hardcopy patent documents. This is the basis for expensive subscriptions or bulk-usage agreements.

Many companies, such as my former employer and many of my current corporate clients, have significantly reduced or eliminated their budgets for value-added databases. Unfortunately, they have also reduced the numbers of company-employed searchers because their technical and legal staff, management, and business leaders believe they can match the use of value-added databases with the patent systems they have available to them. They are missing several key issues when using only free patent databases: Value-added databases are still important for supplementing enhanced patent search systems in some technologies and are invaluable in others. Experienced professional searchers are still critical because they make the best use of value-added databases and enhanced patent search systems in order to deliver the search reports that clients need.

Value-added databases still excel over enhanced patent search systems for searching information that is not disclosed well for easy retrieval by current patent search systems. These include chemical image or line structures and substructures, Markush queries, polymers, protein and nucleotide sequences, and other graphic figures. Database indexers convert this information into content that can be searched in the value-added database systems.

The absence of such facilities in enhanced patent search systems is partially mitigated by the integration of patent classification and citation searching as alternative search approaches. Note that value-added non-patent literature databases, such as Chemical Abstracts CAplus and the corresponding SciFinder product, continue to be of good value because there are few public-domain, free-access, or value-added literature databases comparable to those in the patent space.

The coverage and indexing policies of value-added databases are not sufficient for all types of searches. The value-added database producers have policies that instruct indexers on which and how many patent documents from a patent family to index and on what content to index. These databases generally index records based on only one or a limited number of family members. Indexers may focus particularly on claims, on novel concepts, or on examples rather than index the full specification.

This indexing may not be thorough enough for FTO searches that relate to specific patent authorities (countries or regions) or target subject matter buried in claims. The indexing may not be deep enough to find information critical to success in an invalidity search. In such cases, searches employ a value-added database to identify patent families that should be evaluated further by transferring patent numbers to patent search systems or other sources of patent documents.

I find that value-added database indexing is most useful for patentability searching because the indexing frequently points to novel content. Most searchers would consider valued-added database searches as complementary to, but not substitutes for, full-text searching, especially for FTO and invalidity searching. This is particularly true, for example, for Chemical Abstracts CAplus and Derwent World Patents Index that remain critical for exemplary FTO searches on chemicals and polymers. There are similar enhanced databases in the biological and pharmaceutical areas.